I’d like to talk about those crucial first few hours of a calf’s life, especially during this time of year.

A good start to life is the most essential thing your new calf can have. Unfortunately, if the cow has had a difficult calving (dystocia) then the new calf is already behind the 8 ball, so to speak. Any delivery that takes longer and is stressful on the calf can have lasting effects well into its first few weeks of life.

There are a myriad of articles and books written on the subject of calf delivery, so I won’t

All this to say if your calf had a difficult time being born, then it is greatly stressed, making it much more prone to disease – the bane of the young calf. However, even a calf with a normal delivery can be at risk.

Let’s say your newborn calf is alive, wriggling, and wet on the ground. Success! Lots of work was put into this; the payoff has begun. However, to get that payoff, the calf has to survive. Whether it is a beef calf or a dairy calf, the absolute most important thing that calf can get is colostrum, the first milk from the mother. It is chock full of antibodies and nutrients and getting enough into the calf is the key. All baby calves are basically born without an immune system, and that colostrum provides the start of immunity.

A beef calf can be allowed to nurse, but all dairy calves (and beef calves who won’t or can’t nurse) need to be bottle fed or tubed. (Talk to your vet if you have questions about why all dairy calves should be bottle fed or what ‘tubing’ is). A minimum of two quarts needs to be fed within the first 6-8 hours of life.

(If you cannot get colostrum, then there are colostrum substitutes out there. Just make sure you get a colostrum substitute, not a colostrum supplement! There is a difference.)

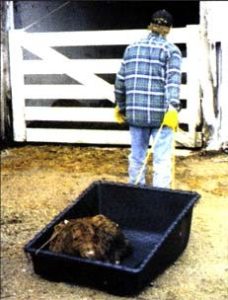

A less than healthy beef calf or a dairy calf need extra attention. Bringing it into a barn or shed or using a calf jacket is essential. I’ve seen to many “calfsicles” that are destined to die no matter how much work you put into them. If you will have a difficult time bringing that calf in, then use a calf carrier or sled.